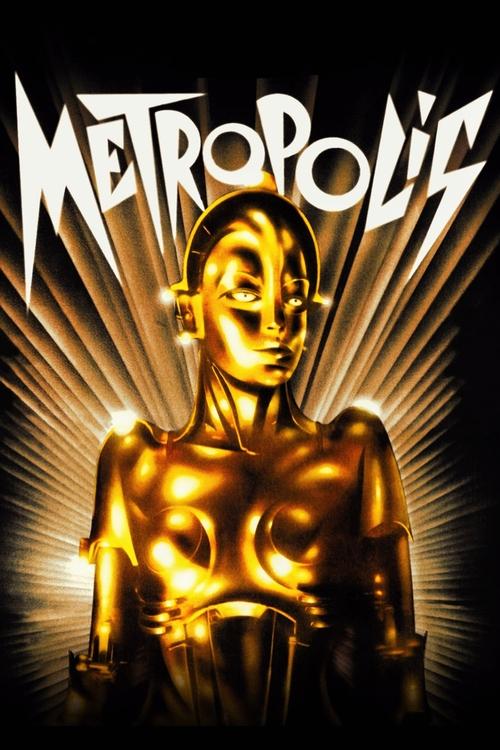

Metropolis

— There can be no understanding between the hands and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.

Metropolis

— There can be no understanding between the hands and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.

Metropolis

In a futuristic city sharply divided between the rich and the poor, the son of the city's mastermind meets a prophet who predicts the coming of a savior to mediate their differences.

The recent restoration based on the almost-complete version found in Buenos Aires, with the recording of the original orchestral score that was composed for the movie - that's the one you want. The shorter ones that are on Internet Archive are OK too, but you miss so much. There's still 8 minutes missing from the recent restoration though, but the restored one looks so much better (it even has the original title cards, which are much more ornate than the ones you see on the shorter versions).

The movie is probably the pinnacle of 20s German expressionist cinema, and Brigitte Helm is terrific. It's an absolute classic, despite some overacting, and if you like this then I'd also recommend the 1922 Nosferatu, Cabinet of Dr Caligari and ANYTHING with Lon Chaney (sr) in it.