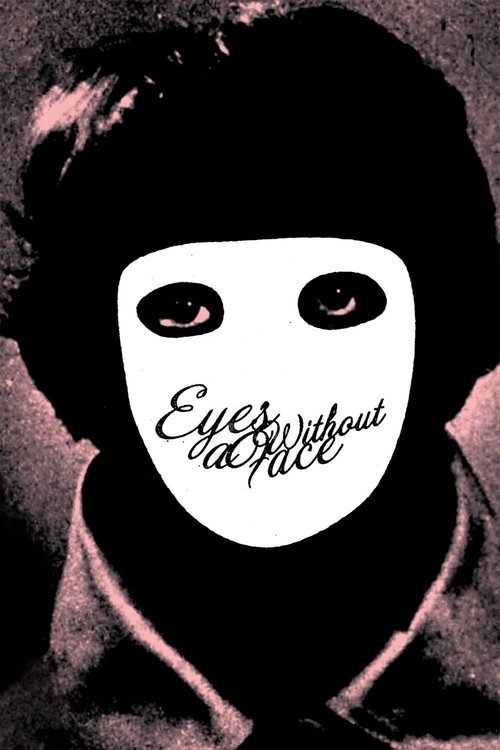

Eyes Without a Face

— Beautiful women were the victims of his fiendish facials.

Eyes Without a Face

— Beautiful women were the victims of his fiendish facials.

Eyes Without a Face

Dr. Génessier is riddled with guilt after an accident that he caused disfigures the face of his daughter, the once beautiful Christiane, who outsiders believe is dead. Dr. Génessier, along with accomplice and laboratory assistant Louise, kidnaps young women and brings them to the Génessier mansion. After rendering his victims unconscious, Dr. Génessier removes their faces and attempts to graft them on to Christiane's.

It is impossible to watch this movie and not realize that we have either seen or read something (or many things!) before, that were clearly inspired by this. And still, this piece shines above them, almost 60 years later. What a great fun it was to experience it!