The Second Mother

The Second Mother

The Second Mother

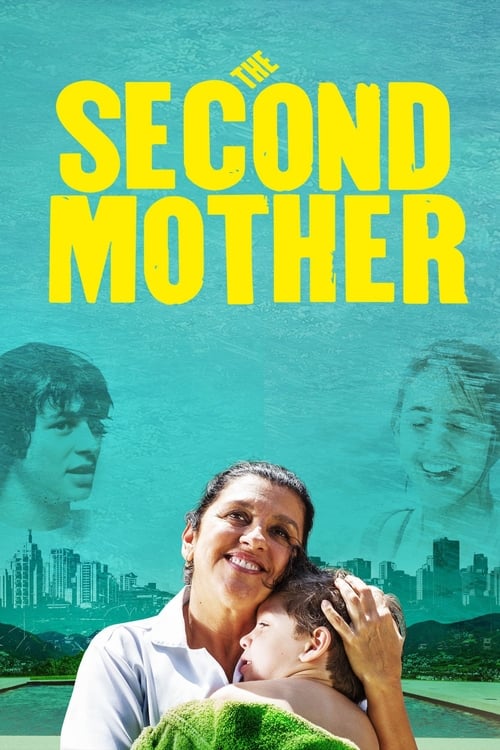

After leaving her daughter Jessica in a small town in Pernambuco to be raised by relatives, Val spends the next 13 years working as a nanny to Fabinho in São Paulo. She has financial stability but has to live with the guilt of having not raised Jessica herself. As Fabinho’s university entrance exams approach, Jessica reappears in her life and seems to want to give her mother a second chance. However, Jessica has not been raised to be a servant and her very existence will turn Val’s routine on its head. With precision and humour, the subtle and powerful forces that keep rigid class structures in place and how the youth may just be the ones to shake it all up.

Uma das melhores produções aqui do Brasil nos últimos 7 ou 8 anos, com a enxurrada de comédia sem graça da Globo entupindo a cota de filme nacional no cinema fica difícil o acesso a filmes de autor para o grande público...